Piecing Sparse Chudy Pre-WW2 Danzig/Poland Origins (read more)

As the story goes, David Chudy was the youngest in a large family which hailed from Poland, but was based in the Free City of Danzig (now Gdansk) for a significant time,

I say ‘story’, since his origins are still very murky. And what little we now know was mostly just hearsay, from a few individuals who are long gone.

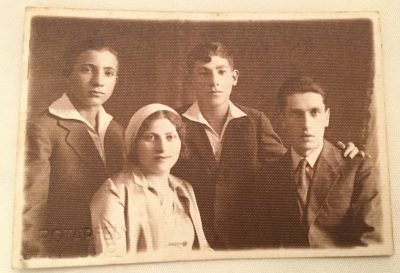

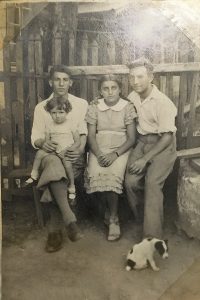

A scarcity of documentation presents little upon which to construct an acceptable timeline. Compounding that, neither he, nor his three surviving older brothers shared more than fragments of their past with their families. The trauma of World War II and the near-complete loss of their family and friends likely contributed to this silence.

David Chudy was born in Wohyń and may have lived elsewhere in Poland initially, but appears to have spent his formative school years in Danzig. David Chudy spoke good German, unsurprising given the city’s large German-speaking population.

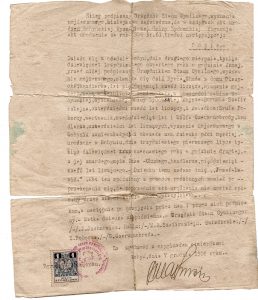

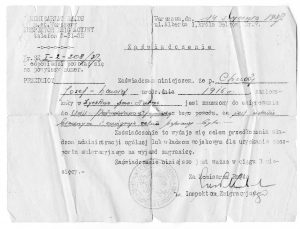

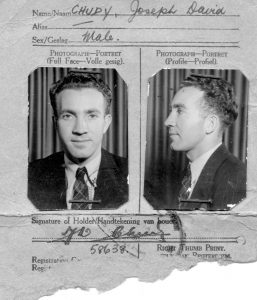

A duplicate birth certificate (1934) and a Polish exit permit from 1937, are the only official items which survive, linking David Chudy to his geographic origins. He appeared to have made his journey to Africa with few other possessions. Presumably a lost passport was also part of this list but this has not been found.

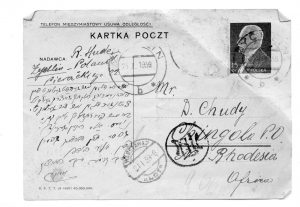

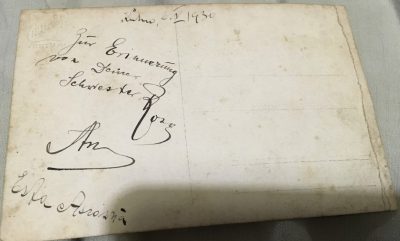

Other than those, a tiny handful photos as well as a few of coded letters round off the entirety of documentation of his pre Africa life. The letters are from 1939, on the eve of the German invasion of Poland. They were mostly Yiddish language, but hand written in Hebrew script, As such, they might have evaded detection but appear to contain little if anything which necessitated secrecy.

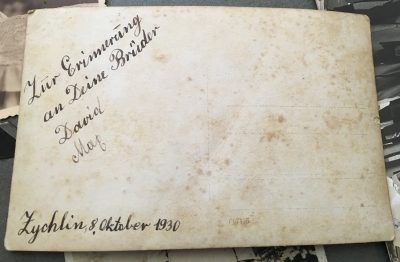

They reveal that he was especially close to one family member. They reveal a mixture of boredom and desperation back in Poland, to find funds and visas for Max (the brother) and his mother, to leave Europe and join David Chudy in Africa. Icek Chudy (the father) had passed away by then and is never mentioned.

Max’s, letters (as per many of the photos) were referenced Zychlin a small town ninety kilometers west of Warsaw. The town, established by a ‘Hasidic miracle worker’, Shmuel Abba, was described as approximately 30% Jewish at that time.

Zychlin was declared ‘free of Jews’ in 1942. Of the estimated 24-28 thousand residents, only 68 Jews survived the war. None of the letters from David Chudy’s brother and mother date from later than German occupation in September 1939. Their ultimate fate is undocumented and unknown.

The exact number of David’s siblings is unclear. The surviving photos feature unidentified individuals who may or may not be relatives.

Tracing his relatives is further complicated by inconsistencies in names. Two brothers used the middle name “Hude,” and the family name had numerous legitimate spellings. First names could have up to four variations, reflecting German, Polish, Russian, and Yiddish influences. For example, “Chudy” (meaning “skinny” in Polish and Czech) had variants like “Chuda” or “Chudigo.” Phonetic spelling used in the Russian alphabet may have contributed to this.

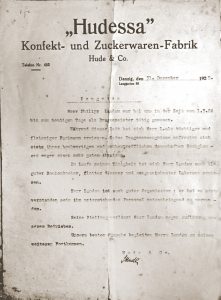

A sweet wrapper and job reference letter to a relative Philipp Landau survived, Both which describe Hude & Co. confectioners and sweet manufacturers on Langgartenstr 58, Danzig. Here the ‘Hude’ spelling of the family name was used.

The Philipp Landau employment reference indicates the cessation of trading of Hude & Co. around December 1925. No explanation is provided.

All building near the Langgartenstr 58 location exist anymore. There appear to be few ‘living memories’ of the place. First the Jews and the Poles were purged and after the war it was the turn of the Germans.

Photographic evidence shows that David Chudy visited London with his brother in 1935. The photo below taken outside Buckingham Palace was only accurately dated, because press platforms are visible in the background. These scaffoldings were a temporary fixture solely the George V Jubilee. David Chudy was 19 at the time.

There is nothing to suggest the reason for the visit to London although it is logical to assume his brothers may have been seeking visas for South Africa where they went shortly thereafter. The ability to travel and a tourist visit to London in those days suggests a threshold of affluence. It also suggests inspiration to reach out and taste the larger world. David Chudy seemingly was not granted entry to South Africa then, if that was indeed what he went there to achieve.

One might infer a level of worldliness on the part of David Chudy who must have spoken English. Letters from Max refer to this as necessary prerequisite (which he lacked), for getting a visa for entry to Northern Rhodesia.

Max and his mother never left Poland. Nor, seemingly did any of the other relatives or friends, who are mentioned in the letters. All it seems, perished in the hands of the Nazis.

Zychlin was declared ‘free of Jews’ in 1942. Of the estimated 24-28 thousand residents, only 68 Jews survived the war. None of the letters from David Chudy’s brother and mother date from later than German occupation in September 1939. Their ultimate fate is undocumented and unknown.

One might infer a level of worldliness on the part of David Chudy who must have spoken English. Letters from Max refer to this as necessary prerequisite (which he lacked), for getting a visa for entry to Northern Rhodesia.

Max and his mother never left Poland. Nor, seemingly did any of the other relatives or friends, who are mentioned in the letters. All it seems, perished in the hands of the Nazis.

Zychlin was declared ‘free of Jews’ in 1942. Of the estimated 24-28 thousand residents, only 68 Jews survived the war. None of the letters from David Chudy’s brother and mother date from later than German occupation in September 1939. Their ultimate fate is undocumented and unknown.

The exact number of David’s siblings is unclear. The surviving photos feature unidentified individuals who may or may not be relatives.

Tracing his relatives is further complicated by inconsistencies in names. Two brothers used the middle name “Hude,” and the family name had numerous legitimate spellings. First names could have up to four variations, reflecting German, Polish, Russian, and Yiddish influences. For example, “Chudy” (meaning “skinny” in Polish and Czech) had variants like “Chuda” or “Chudigo.” Phonetic spelling used in the Russian alphabet may have contributed to this.

A sweet wrapper and job reference letter to a relative Philipp Landau survived, Both which describe Hude & Co. confectioners and sweet manufacturers on Langgartenstr 58, Danzig. Here the ‘Hude’ spelling of the family name was used.

The Philipp Landau employment reference indicates the cessation of trading of Hude & Co. around December 1925. No explanation is provided.

All building near the Langgartenstr 58 location exist anymore. There appear to be few ‘living memories’ of the place. First the Jews and the Poles were purged and after the war it was the turn of the Germans.

Photographic evidence shows that David Chudy visited London with his brother in 1935. The photo to the left, taken outside Buckingham Palace could be accurately dated, because press platforms are visible in the background. These scaffoldings were a temporary fixture solely the George V Jubilee. David Chudy was 19 at the time.

There is nothing to suggest the reason for the visit to London although it is logical to assume his brothers may have been seeking visas for South Africa where they went shortly thereafter. The ability to travel and a tourist visit to London in those days suggests a threshold of affluence. It also suggests inspiration to reach out and taste the larger world. David Chudy seemingly was not granted entry to South Africa then, if that was indeed what he went there to achieve.

One might infer a level of worldliness on the part of David Chudy who must have spoken English. Letters from Max refer to this as necessary prerequisite (which he lacked), for getting a visa for entry to Northern Rhodesia.