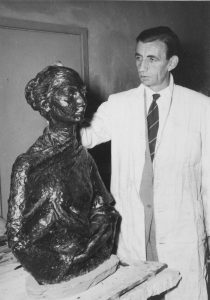

First Lost Wax Bronze Casting South of the African Equator – 1960 (read more)

David Chudy started to produce sculpture in earnest, not only when he had the space and facilities to create it, but also room to store it afterwards. In 1960 he had a purpose built studio space as well as an industrial property to work with.

He worked primarily in clay. Clay is an unstable medium, which self-destructs as it dries out. It is necessary to make a mold very soon after the artistic work is done. The work is not complete, until it is cast in a durable material, most notably bronze. The lost wax process is the way this has been traditionally achieved, though this had never been accomplished in Africa, south of the equator (or anywhere in Africa except in antiquity).

Romolo Fiorini (1916-1993) came to Rhodesia from the UK in the early 50’s, seeking employment. Romolo was the son of Italian immigrant to England, Giovani Fiorini, born 1876. Giovani started a bronze foundry in Battersea, London in 1909, which was taken over by his son Remu. Giovani Fiorini’s foundry was responsible for casting the iconic sculpture of David Livingstone which still stands by the Zambezi at Victoria Falls. Remu was a lifelong friend of Henry Moore, and his foundry cast a lot of Moore’s work. Other sculptors included Henri Gaudier Brzeska, Eduardo Paolozzi, David McFall, Anthony Caro, Alberto Giacometti and many others.

Romolo Fiorini had joined the Merchant navy before and served during World War II. But he had worked in the foundry earlier. Romolo knew how to do ‘lost wax’. David Chudy gave him a job as corporate manager at his company, Terrastone, confident that they could both crack the process locally, so he could cast his own work at will.

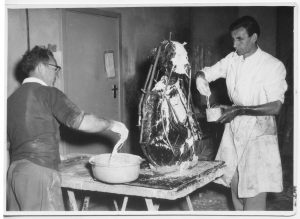

It was necessary to improvise many of the standard materials and tools that were not available. Crushed up bathroom sinks were used for ‘grog’ for the casting core. Improvised heat-proof bricks were used around a large excavated hole in the ground. Paraffin oil was pumped in with compressed air, and it burned, shaking the ground much like a buried jet engine would (see photo below).

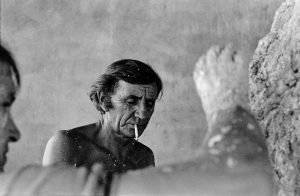

The biggest fear in pouring the molten bronze was that air gaps would be left in the cast, leaving some parts of the work unformed, ruining the entire cast. And in terms of safety: moisture or pressure backup could explode molten metal over people close to the process.

The photo series from the first lost wax process reveals some of the procedure, including special pipe-channels, which are added to ensure a full flow of metal as well as venting during the pour. At the end these need to be sawn off. Great anticipation and tension can be seen in the faces of those watching because a successful outcome cannot be guaranteed.