African Adventure & Unsolved Royal Mystery (read more)

King Mwanawina Lewanika III of Barotseland, the Litunga, ruled the Lozi people until his death in 1968. Barotseland, in the form of a British Protectorate at that time, had been an empire lasting a millennium, at times reaching the size of Texas. It included 33 different ethnic groups spread across Botswana, Zimbabwe, Angola, Namibia and Zambia.

Extremely remote, as it was, at the turn of the last century, Mwanawina’s predecessor, Lubosi Lewanika (1878-1916), was not in the least parochial. He visited London in 1902, where he was granted audience with the newly crowned King Edward IV and the Prince of Wales. Earlier, he had sent gifts (huge elephant tusks), along with a petition, to Queen Victoria. But he discovered later that they had never arrived. They had been appropriated by the directors of the British South Africa Company, who mounted them in their board room. Dealing with the British had been a mixed experience. There had been some token recognition at first, but disdain and betrayal had followed, probably in greater measure.

In 1964, during British colonial rule, Barotseland under Mwanawina was corralled by local politics as well as the British, but he voluntarily agreed that it be integrated into a greater Northern Rhodesia. The formal agreement, which was to reciprocate his mostly autonomous decision to participate, was abrogated by the Zambian government upon independence in 1970. Thereafter Barotseland was no longer a formal geopolitical entity in any significant form and it was effectively sidelined on the world stage. But, by virtue of its long history, it persists as a source of inspiration and remains a distinct and persevering cultural entity.

After David Chudy’s death in 1967, the sculpture of the king existed for a while in anonymity, in storage in the form of a hollow cast. Shortly after, to honor his memory, it would be cast again as a positive, wherein it could be appreciated once again.

Nice as that was, until recently, there seemed to be no particularly pressing reason by anyone to question when the sculpture was made and the circumstances under which it was produced. For a casual bystander, the idea that David Chudy had spent 8 years in Northern Rhodesia (up to 1947), would be sufficient to assume that a straightforward ‘back-story’ to this engagement must exist. Initially this seemed to just be ‘another undated sculpture in the collection’, but digitization and viewing of an ancient 8mm film shot by David Chudy stimulated the imagination and prompted further research.

The low quality, silent color film (included in the gallery below) features African ceremonial dancing. Based on the distinctive clothing of the dancers, the action in the reel was clearly not set in Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). However, a small clip within it tied one reel of footage to the Mwanawina sculpture. That clip showed a road within a compound with a large banner sign which read ‘King Lewanika’.

Later on in the reel were shots from a small airplane overflying what appears to be the Zambezi River. And then, at the very end we find scenes clearly revealing the sub-alpine environment of the Eastern Highlands in Zimbabwe (nothing similar exists anywhere in Northern Rhodesia/Zambia). That all of this is on one uncut reel is fairly convincing evidence that that the work had been produced after 1947, when David Chudy had relocated to Southern Rhodesia. He had visited Salisbury once before 1947, but had not been to the Eastern Highlands.

The most significant finding from viewing this film was a feeling that this sculptural project had been of much greater importance than formerly thought. Considering the logistics alone, the prospect would have been either a 2,000km/five-day car trip there and back, on very challenging roads, or – as is now assumed – a delicate clay original would have had to have been transported in a small commercial airplane back to base – or else cast into a positive on location (with all the cost and logistics that entailed).

The location where the sculpture was produced is remote, either at Sefula or the King’s dry-season residence Lealui, in the far west of Zambia, close to Angola. It is unlikely that at the time there were high-volume scheduled commercial passenger flights to this out-of-the-way place.

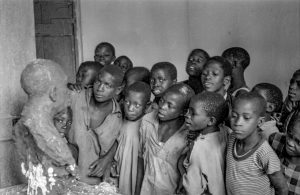

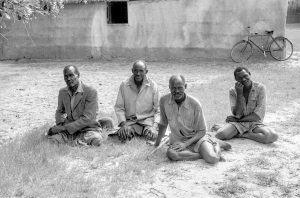

Subsequently, the discovery of some still, film negatives mirrors some of the scenes of the ‘moving image’ reel, but interspersed with them are images of the King and some of his entourage admiring the sculpture. Some of these photos are featured here.

Common sense suggests that the production of this bust was paid commission work, rather than a free artistic project. However, no evidence has yet been found indicating who assigned the work and why they would have assigned it. It might be logical to speculate that this work would have to be dispatched to be cast in bronze overseas, because nothing like that was available in Southern/Central Africa. But again, no documentation supports this idea. David Chudy’s first venture into lost wax bronze casting would have to wait till at least 1960.

Meanwhile, none of King Mwanawina Lewanika’s descendants who have been approached have knowledge about this. Gratifyingly a few people in the photos were recognized, but they are no longer alive to share their experiences. The background to this historic sculpture session and its purpose remains a mystery.

King Mwanawina Lewanika III was bestowed with the title of the Knight Commander of the British Empire (KBE), c. 1st January, 1959. An amateur Sherlock Holmes might reason that were a bust were to be commissioned to commemorate occasion, for the benefit of the British themselves, a British sculptor would have been the logical first choice to do this – on British soil, while Mwanawina was in the UK receiving his honor. Speculation is a necessary evil in the absence of evidence, but it is also possible that David Chudy was assigned, on location in Africa to honor that event with a bust. That would be the more adventurous scenario. Were the sculpture assigned by the King himself, for his own benefit, it is hard to think it would not be known in the family.

1959 certainly does seem a reasonable place to peg the work in the context of David Chudy’s developing style. Whatever the story, it is still reasonable to suspect that this is not the only copy in existence. For all we know, a bronze might well be subject to dusting by janitorial staff, at this very moment, in a stuffy, paneled room, somewhere in UK.