The Unexpected Photographer (read more)

A camera seems to have accompanied David Chudy most of his adult life, but there is little indication that he ever entertained a serious role as fine art, or documentary photographer – and nor did anyone else around him.

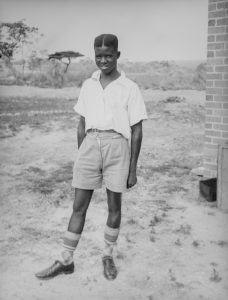

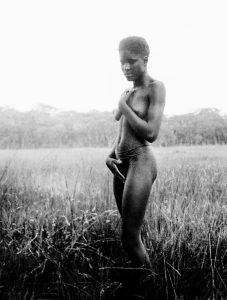

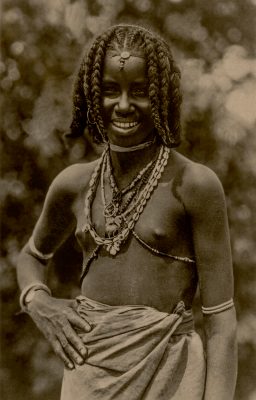

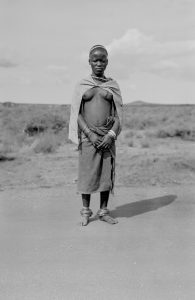

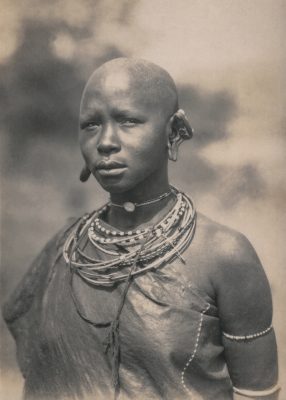

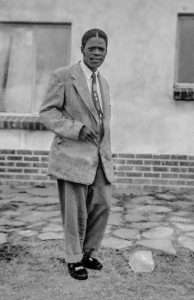

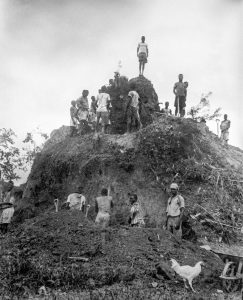

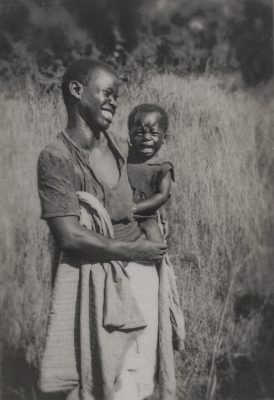

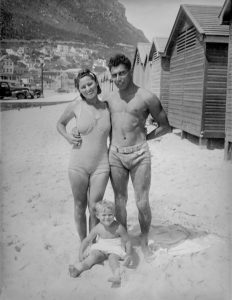

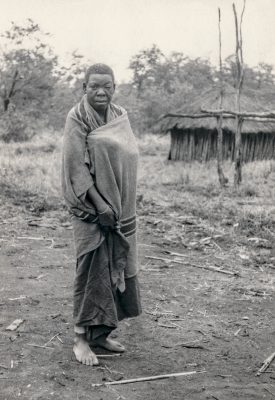

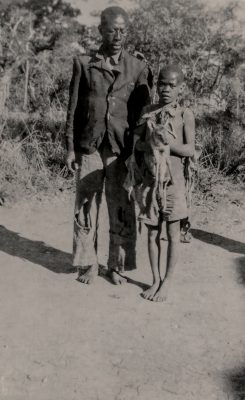

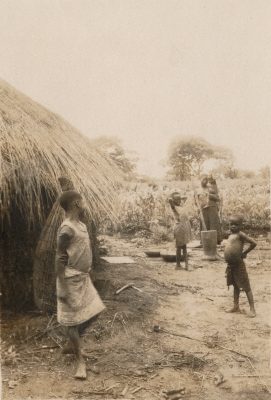

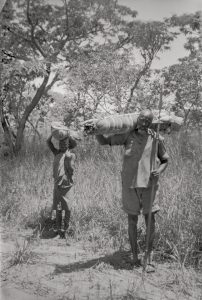

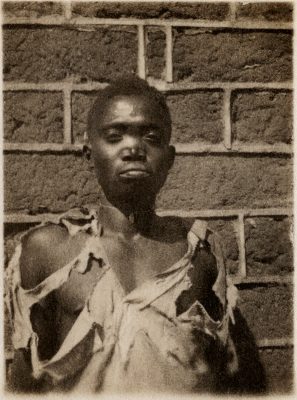

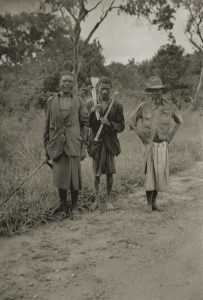

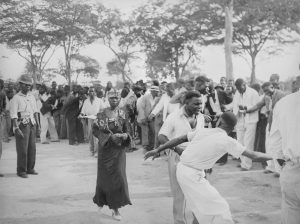

However, an extraordinary collection of David Chudy’s early photography was only recently identified. The original negatives (1938 – early 1950’s) reveal an eye, compositional treatments and narrative subject matter which begins to compete with the work of other celebrated photographers of the age. This collection comprises photos from the early days in Northern Rhodesia 1938 till the mid 50’s.

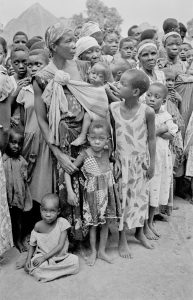

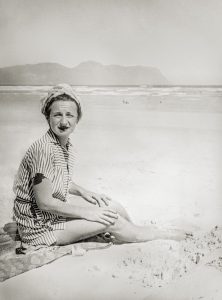

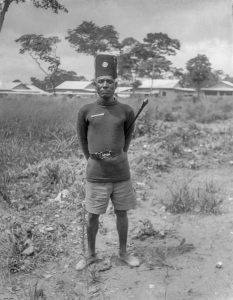

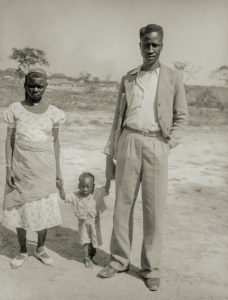

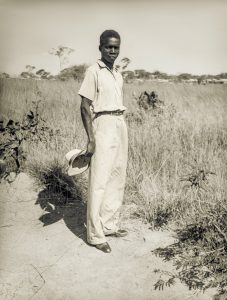

It ranges from formal portraits of people – from familiar faces to strangers, of all classes and races – to landscapes, historically interesting cityscapes and events (colonial and tribal).

As a series, the interest is significantly enhanced by its documentary/historic content as well as the biographical context it lends David Chudy’s own painting and sculpture. It is rich with insights into his developing artistic eye and helps us see his other work anew.

The bulk discovery of early black and white negatives was unanticipated but a surprise technically, because negatives contain more tonal/visual information than prints. That said – these negatives were mostly in very poor condition, having endured very poor archival storage, in a tropical environment for up to 85 years. The damage presented as a challenge, prompting the application of expert scanning and digital processing to extract the maximum fidelity possible. The straightforward rarity value of these images justified bringing them back to life, even in the cases where the pure photographic merit was lacking.

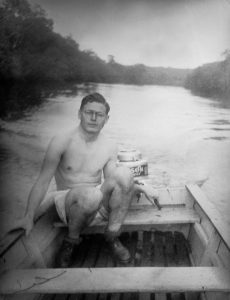

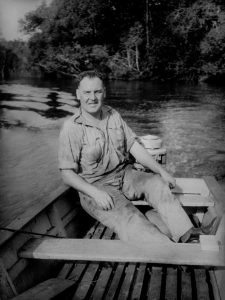

Although he clearly devoted a lot of energy and enthusiasm to his photography, David Chudy never committed to being photo technician. The prevailing perception was that processing and development were crucial in photo artistry. There is no evidence that he enlarged or showed off his photos in public, or to friends. Had he done so, he would have used a tripod more often – although that does cramp the style when striving to capture the moment.

Advanced digital tech cannot exceed the limits to the film stock and inferior lenses/photo equipment of the day but technically, many of the images might be said to reach a threshold of contemporary visual fidelity, when it comes to storytelling .

His friendship with pro photographer Peter Fernandes after the 1947 move to Southern Rhodesia would have impressed upon him, the levels of technical proficiency/investment in equipment which were expected for entry in the establishment photography world. The sense that he was had limited technical prowess might have prompted a retreat from his former passion for the medium. His growing competence in painting and sculpture likely satisfied his creativity moving forward.

Oh a technical level, the bulk of his early photography was exclusively on a range of discontinued film stock formats. It was exclusively monochrome roll film, loaded into what appear to be, a range of early fold out cameras. The negative sizes varied but some of the film approached ‘view camera’ size although unless a tripod was used, that level of sharpness was not achieved.

The post war ‘miniature format revolution’ did not pass David Chudy by. After the move to Southern Rhodesia he transitioned almost exclusively to the use of color 35mm film, now being the proud owner of a highly portable Leica IIIg camera. The major equatorial African safari in the late 50’ was documented almost exclusively with that camera. Film stock was the original much vaunted Kodachrome.

Black and white was forgotten about thereafter including the next trip to the Far East. But what also dropped out of David Chudy’s photography was the former passion for producing ‘environmental imagery’: meaning that for cinematic visual context, the subject of the image is composed with a lot of space around it. His work thereafter devolved to a standard close cropped snapshot style. ‘Travel memories’ with fewer aspirations to satisfying high art aesthetics.

So – this early photography should be celebrated for what it was – not what it promised to be. And had this image trove not been explored there would have been no reason to even think of adding photographer to David Chudy’s resume.