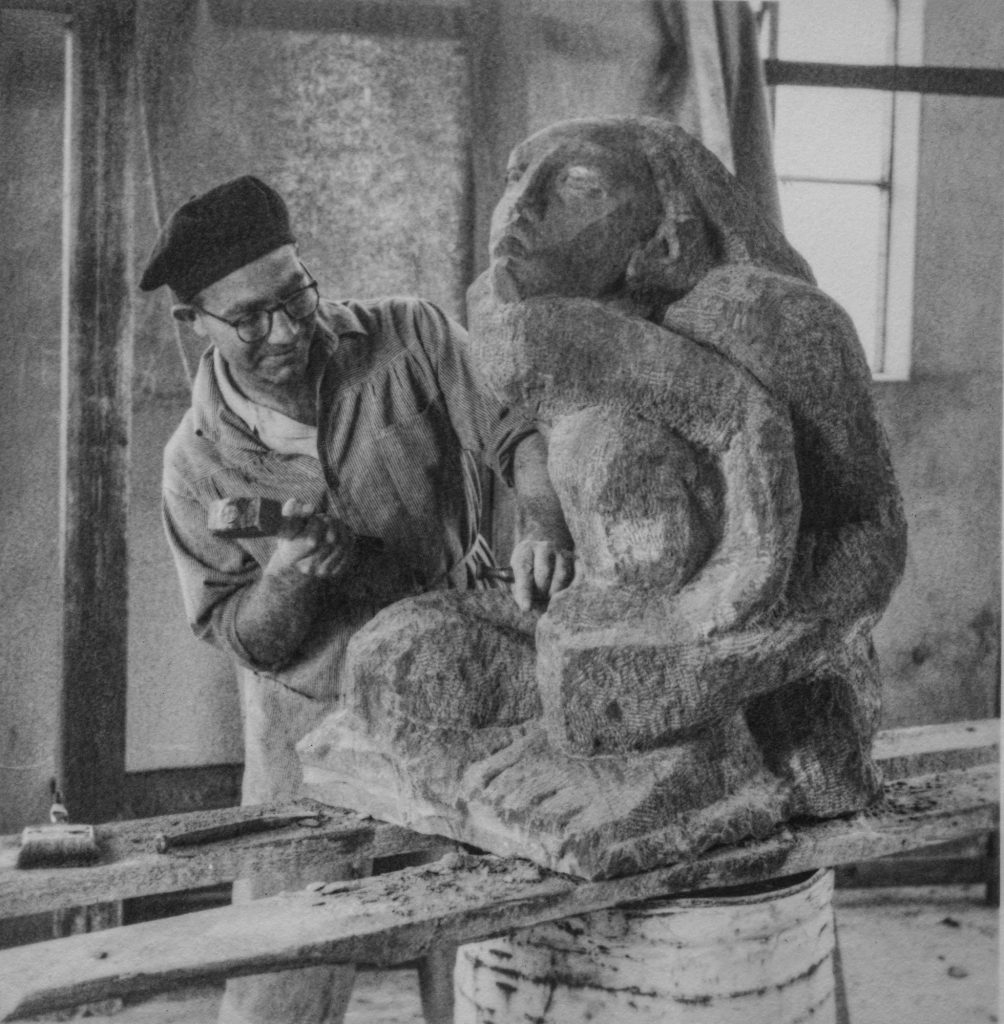

The story of David Chudy’s art needs to be told…because he didn’t get to tell much of it himself.

Of course he speaks to us directly through his art, but so often, for an easy understanding of an artist’s contribution and their place in art history we rely on echoes and re-telling of the artist’s career – as well as their ascent of the ladder of social notability.

David Chudy was an off-the-grid artist. We are denied a prefabricated assessment of his art through the eyes of others. That said, some of his art is famously public, celebrated as city landmarks; but they are unsigned and never subjected to formal fine art assessment. An artist’s dialog with his critics is often revealing.

Why didn’t he persist to pursue recognition or a public artistic career? For people who knew him later in life, this failure (if indeed it is a failure) didn’t stem from a desire to avoid the limelight or accountability. Not that he appeared to be uninterested in what other people thought of his work, it was just not what was driving him. Chudy’s other accomplishments probably justify the label of ‘polymath’ and a common sense conclusion might be that he was simply too busy doing other things.

One might wish to delve deeper into his background and childhood for more profound reasons for this approach, but information about his early life in Europe is sparse to nonexistent. Chudy left Poland for Africa, arriving just before World War II. It is from the sub-tropical backwaters of Northern Rhodesia, near Congo where we start to get an idea of the man.

There were no artistic or cultural institutions in that part of Africa. Were he to have wanted to been seen as an artist, there was nothing he could play to. As a twenty-two-year-old European he was building his artistic career from scratch. Even as he posted for sefies, the standard Western artist lifestyle was wholly inappropriate in these primitive conditions.

Against a backdrop of what was then the angry onset of war in Europe (and his family’s vulnerability and eventual demise in the face of it) the stark reality about acceptance and equanimity presented itself. Although a world away, beyond the ghettos and battlefields, the indigenous African people here were on their own front line. They were on the threshold of being catapulted into an uncharted technological future. Like it or not, the simple rural tribes person was having to calibrate his or her vision to accommodate massive changes. In the context of this, why then should Chudy, a fellow flesh and blood human not accept a fraternal kinship?

Rather that ignore his immediate environment and behave as if he were destined to be a fashionable artist in Paris, his destiny seems to have been to welcome intellectual and artistic leaps of similar significance to his African brethren.

While he produced art his entire life, he also threw himself into being a successful entrepreneur in the marble and terrazzo business. He supplemented his very limited education and became a self-taught scientist, doing self-funded research into bat echolocation. This was evolving to include experimentation to assess the potential for decoding ‘dolphin speech’ – before his untimely death in 1967, aged 51.

He never questioned his own motives as an artist and was highly prolific. Despite his involvement in other areas, his art was always core to his being. Had his life not been cut short at his creative prime, he would surely have taken time to foster a public artistic persona.

We often say that art speaks for itself. Perhaps so? If his art is still speaking there is nobody but ourselves around now, to hear it.